They're not yet available on the mass market, but environmentalists and tech gurus are already hailing them as a reliable way to power everything from consumer electronics to next generation electric vehicles. Experts suggest they'll help society transition to a greener, less carbon-dependent economy. They're also notoriously difficult to create.

But Corning's deep knowledge of both ceramic science and manufacturing has the company poised to break through some of the practical barriers and capitalize on the next generation battery trend as it unfolds over the coming years. Why the excitement around lithium metal batteries?

For starters, they're the first step-change in mobile energy storage since rechargeable lithium-ion batteries came on the scene nearly 30 years ago. Enthusiasts believe lithium metal batteries built with ceramic separators offer longer battery life, and in some cases lighter form factors, as well as improved thermal stability largely due to the reduction of flammable liquids that are in contact with lithium metal.

To understand why, look at basic battery structure. All batteries contain layers that create an environment for complex, electro-chemical reactions – which, in turn, release energy.

Lithium-ion batteries – like the one powering your phone and tablet right now -- feature a reducing anode (typically made of graphite) and an oxidizing cathode (made of lithium and other chemicals). A porous polymer separator containing liquid electrolyte prevents these two layers from touching. Migration of lithium ions through the layers prompts an electro-chemical reaction which, in turn, releases the energy to power a device.

Lithium, a lightweight metal, would be the ideal anode in battery applications as it has no inert structure like graphite that takes up space inside the battery. But it's highly reactive and prone to forming "dendrite" spikes as the battery is used and recharged. These can degrade the traditional separator used in today’s lithium-ion batteries causing internal short-circuits that lead to failure of the cell and in some cases a fire.

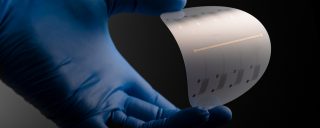

Lithium metal batteries are also built-in layers. The solid electrolyte separator and anode layer – made of pure lithium metal as the name implies-- can also be very thin, making the battery smaller than lithium-ion batteries with the same energy (runtime or range).

The challenge comes in getting the right mix of elements to safely harbor the massive amount of energy passing through a small space – then manufacturing the battery in an affordable way. Over the past five years, Corning scientists have been testing promising new solutions to both problems.

On the materials side, Corning is particularly interested in lithium garnet, so named because its crystal structure resembles that of the deep-red gemstone. Lithium garnet is a good conductor of lithium ions and is an effective solid replacement for polymer separators containing liquid electrolytes, said Dr. Scott Silence, Ribbon Ceramics program director.

What's more, lithium garnet is stable against lithium metal, the thin, lightweight anode material for the batteries.

"Lithium garnet is one of the very few materials that can stand up to lithium metal as an anode and not degrade and limit the life of the battery," he said. "When it's stable, you can use it and recharge it many times."